-

Does the rate of change of carbon emissions targets give some cause for optimism?

Date posted:

-

-

-

Post Author

Patrick LaveryCombustion Industry News Editor

-

-

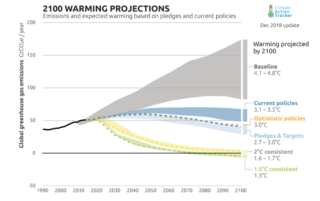

According to the estimates of Climate Action Tracker (CAT – a consortium of the non-profit organisation Climate Analytics, the non-profit New Climate Institute, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research) current policies around the world to limit carbon emissions will see global average temperatures rise by between 3.1-3.5oC by 2100, with the median estimate being 3.3oC. These estimates are far in excess of the 1.5-2.0oC target of the Paris Agreement on climate change, and the differences in impacts around the world from such a large exceedance would be stark and severe. Even the differences between 1.5oC and 2.0oC of warming would be profound, as detailed in last year’s IPCC report ‘Global Warming of 1.5oC’, a short summary of which was published on the IFRF’s website last year.

However, let’s remember that those CAT estimates are based on policies currently in place across the world. If the unconditional pledges given by different countries are considered, the projected temperature increase by the year 2100 ranges from 2.7-3.0oC. This reflects the fact that not all unconditional pledges have been converted into policy to date. It is also worth noting that there are also conditional pledges, usually dependent on action from other countries, not factored into these projections, though the ‘optimistic policies’ scenario factors in planned policies.

While the gap between the warming the world would experience based on current policies (or even pledges) and the Paris targets is cause for deep concern, and climate impacts are already being felt from region to region, there is reason to be somewhat more optimistic about what the future holds. This is because policies are likely to become stronger in future years.

There are numerous signs to support this. The first is that countries around the world have, over the past 20 years, already been improving their targets, albeit non-uniformly and with some notable exceptions. Let’s consider three specific examples: the UK, China, and the USA.

In 1997 the Kyoto Protocol came into effect, and the UK’s target was a reduction of 12.5% in carbon emissions from 1990 levels by 2012. (The target was met.) In 2008, the UK government set a new target of a 34% reduction by 2020 (from the 1990 baseline) and an 80% reduction by 2050. (The 34% by 2020 target was met in 2016.) In 2015, as part of the EU’s pledge towards the Paris Agreement, the UK signed up to reduce carbon emissions by 40% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and in June this year, the UK government set a new target of being net carbon neutral by 2050.

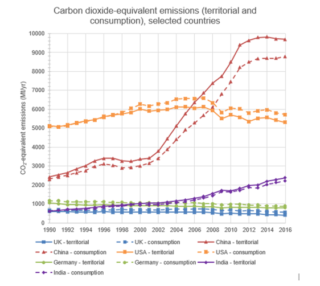

While the UK has been a leader, along with other European countries, in setting climate change targets, there has been criticism that de-industrialisation within the developed world has simply shifted emissions to other countries, allowing developed countries to claim reduction achievements while global emissions have increased. There is some truth to these claims, as can be seen in the comparison of countries’ ‘territorial’ emissions and those adjusted to consumption (including the import and export of ‘embodied emissions’), data being taken from the Global Carbon Project. Yet even considering consumption-adjusted emissions, many developed countries have made considerable progress in their emissions, as the same chart shows. (Still, one might reflect that shifting production to countries with worse emissions intensities was not a sound move in terms of the climate.)

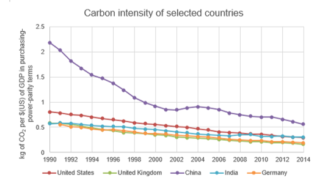

China didn’t set a Kyoto Protocol target. Its entry onto the international stage for setting carbon emissions reduction targets was in 2009 as part of the Copenhagen Accord, when it announced a goal of reducing the carbon intensity of its economy – i.e. the amount of emissions per unit of gross domestic production – by 40-45% below 2005 by 2020, and by having 15% of its energy generated by non-fossil sources. By setting an intensity target, China could expand its economy and increase its absolute emissions while making technological improvements that would be at least some reflection on improved environmental performance. This was a compromise target, which saw absolute Chinese emissions rise dramatically even while meeting its target three years early, in 2017. As part of the Paris Agreement in 2015, China improved and added to its targets, setting a peak in emissions by 2030 and further intensity reductions of 60-65% on 2005 levels by 2030, and raising the non-fossil fuel share to 20%. (A chart of selected countries’ emissions intensities has also been provided, using data from the World Bank, though the data only stretches to 2014. It must also be read with some caution – the percentage of a country’s economy that comes from industry varies – countries with higher shares of industry in their overall GDP are expected to have higher carbon intensities.)

The case of the USA is more complicated. It didn’t ratify the Kyoto Protocol after agreeing to a reduction of 7% in emissions from 1990 levels, and, despite some reports to the contrary, did not meet those targets. In Copenhagen in 2009, the USA set a target of a 17% reduction from 2005 levels by 2020 (and by 2017 was estimated to have reduced emissions by 14%), and for the Paris Agreement in 2015 set a target of 26-28% reductions by 2030 from the same 2005 baseline. The Trump administration has subsequently communicated its intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, though formally the USA is still a part of it.

This sample of the evolution of targets shows that progress has been made, though haltingly and with some steps backwards. It also shows that targets do generally result in improvements. Extra support to the idea that targets will further improve in the future comes from reports of government and political announcements, as well as other news. It is being assumed by business leaders in Australia that the country will set a net carbon neutral target for 2050, for instance, and there was much talk that the EU would this year set a similar target. While the EU did not set that target, it would not be a surprise if it was adopted sometime in the next two or three years. China is expected to set more stringent emissions targets in the coming years, with the most recent indications being a peak in 2025. In the USA, sentiment amongst young Republican voters is that their party should be setting more ambitious climate change policies, while the target of all Democrat presidential candidates is carbon-neutrality for the country by 2050, if not before.

Improved emissions targets have come despite the problem of ‘the tragedy of the commons’, where there is a temptation for individual nations within a group not to act when it is in their collective interest that action is taken overall. It might be expensive to shift to cleaner forms of production, and a nation may decide that if enough other countries make the change, they themselves will not have to act. (This may not be 100% accurate from 2005 levels for climate change – it has been suggested that some countries may be advantaged under a warmer world – but it is generally applicable.) In some ways, it is surprising that such advances as we have made have been achieved. That emissions targets have improved and are likely to continue to improve is the result of a mix of political pressure on the part of the populace (and between nations), governments heeding the advice of experts, technical development, and a growing conviction that it will be more expensive not to act than to act.

Whether future targets will be sufficient to lower estimates of future temperature changes to meet the 1.5-2.0oC target of the Paris Agreement is difficult to predict. The technical challenge is immense, especially when applied across economies (including agriculture, land-use, shipping and aviation, and buildings, on top of industry) and if living standards across the world are to improve through the years. Countries that have set ambitious targets might struggle to meet them. The track record is relatively encouraging, though, and the trends in the changes to carbon emission reduction targets suggest that there is a case to be cautiously optimistic.