-

Airlines under increasing scrutiny for spiralling carbon emissions

Date posted:

-

-

-

Post Author

Philip SharmanIFRF Director

-

-

Question: Did you know that airlines were the biggest carbon emitters in four European countries in 2018 and were among the top 10 emitters in another 12, increasingly occupying the top positions previously dominated by coal-fired power generation and heavy industry?

No? Me neither! This fact emerged from analysis of EU emissions data by Transport & Environment (T&E) – an umbrella for non-governmental organisations promoting sustainable transport in Europe – published last month.

In 2018 easyJet was the biggest carbon emitter in the UK, Ryanair in Ireland, Norwegian in Norway and SAS in Sweden under the EU emissions trading system (ETS), which covers emissions from flights within Europe and from the industrial and power sectors.

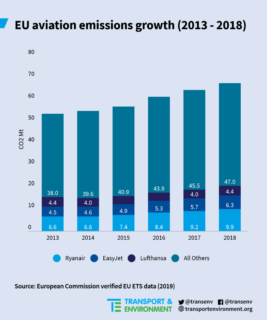

Furthermore, in April T&E revealed that Ryanair had become the first airline to enter the top 10 carbon emitters EU-wide, emitting 9.9 MtCO2. It is particularly sobering to note that the nine bigger sources were all lignite-fired power stations, many of which are slated to close in the next few years: Meanwhile, Ryanair’s emissions are increasing – up 49% from 2013 – meaning that the airline will continue to climb in the rankings unless action is taken to rein in its emissions.

One person who wasn’t surprised by these figures is Andrew Murphy, T&E’s aviation manager. “Airlines are the new coal. Given how under-taxed and under-regulated the aviation sector is, it comes as no surprise that they are in the top 10 emitters. Unlike cars, trucks, vans and trains, airlines pay no tax on their fuel and have no limit on their emissions growth. EU governments need to end the kerosene tax holiday and demand real emissions cuts from aviation.”

European airlines pay a minimal cost for their emissions compared to what they would pay in kerosene tax – from which they are currently exempt. For example, a flight from Oslo to Rome adds under €4 to their operating costs, according to T&E calculations. The total cost to airlines of being in the EU ETS is about €700 million a year, while they actually save around €9 billion a year thanks to their kerosene tax exemption.

Airlines’ carbon emissions grew by 4.9% on flights within Europe last year – in contrast to the other sectors covered by the EU ETS, such as coal and cement plants, which declined by 3.9%. Carbon pollution from flying in Europe has risen by a staggering 26% in the last five years, far outpacing any other modes of transport.

T&E are lobbying that airlines should have their free emissions allowances in the EU ETS removed, start paying tax on their kerosene, and be subject to VAT on their tickets – like all other transport sectors. Radically cutting aviation emissions would also require a wholesale shift to (bio)synthetic kerosene or perhaps hydrogen, produced from renewable electricity and maybe, in the longer term, direct carbon capture from the air.

However, rather than taxing and regulating aviation emissions, governments are pursuing a new and somewhat controversial UN offsetting scheme for aviation, known as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), which will allow aviation emissions to continue growing. However, there are ongoing and serious doubts concerning the environmental effectiveness of carbon offsets, and airlines can emit even more carbon by buying ultra-cheap offsets, investing in environmental projects instead of reducing their own carbon footprint.

Meanwhile, in Sweden a public campaign for people to fly less – ‘Flygskam’ – continues to have an impact. Last month Swedish regional airline BRA cited flagging demand for internal flights when it announced plans to lay-off around a third of its staff. Previously the company, which operates 10 Swedish airports, had said its year-on-year passenger numbers dropped for seven months in a row. Meanwhile, passenger numbers at the state train operator increased to a record 32 million last year.

There is growing public and political support for ending aviation’s special treatment. All of the major candidates for the European Commission presidency (to be resolved by November) have come out in favour of taxing kerosene, meaning that the next Commission will have a strong mandate to act. Even as I sit writing this IFRF Blogpost, EU finance ministers meeting in the Hague are discussing this very situation, with the ministers from the Netherlands and France trying to convince fellow European nations to end tax exemptions on jet fuel and plane tickets, as part of a drive to make the EU carbon neutral by 2050. All strength to their elbows – it will be interesting to see if they succeed…

However, it should be noted that the figures above only reflect emissions from flights within Europe, which is the current scope of EU ETS. They exclude emissions from flights from or to Europe, and, obviously, do not include national and international flights elsewhere in the world. A broader scope, for example, covering all flights from Europe, would produce different figures.

So, what is the picture from a global perspective?

Aviation accounts for around 15% of global oil demand growth out to 2030, according to the International Energy Agency’s ‘New Policies Scenario’ (as presented in the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2018 – see IFRF Blog last December), a similar growth to that for passenger vehicles.

Over this same timeframe, aviation’s contribution to total global energy-related CO2 emissions will rise from 2.5% (today) to 3.5%. While some may choose to downplay this contribution as relatively minor, the 2018 ‘Special Report’ from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C – see IFRF Blog last October – noted that “shipping and aviation are more challenging to decarbonise, while their demand growth is projected to be higher than other transport modes. Both modes would need to pursue highly ambitious efficiency improvements and use of low-carbon fuels. In the near and medium term, this would be advanced biofuels while in the long term it could be hydrogen as direct use for shipping or an intermediate product for synthetic fuels for both modes”.

In a future IFRF Blog we will take a look at these various options, i.e. the scope for further efficiency improvements in aero propulsion systems, and low-carbon alternatives to kerosene as aviation fuel (including aviation biofuels – so-called ‘sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)’ – and the potential role for hydrogen in aviation in the longer term).

Meanwhile, if you are jetting-off somewhere nice for your summer holidays, have a great time (but perhaps consider carbon offsetting your flight using a certified, credible, ‘gold-standard’ offsetting scheme – not a perfect solution, but all there is at present)!