-

Energy from Waste and the Circular Economy

Date posted:

-

-

-

Post Author

Philip SharmanIFRF Director

-

-

![]()

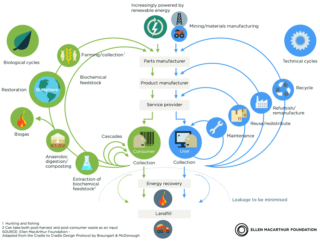

Last November, IFRF’s Italian Flame Research Committee organised a successful Topic Oriented Technical Meeting (TOTeM 46) in Pisa on the subject of energy-from-waste (EfW). Much discussion was had about how EfW fits within the context of what is often described as the ‘circular economy’. The above diagram from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation captures nicely the integration of ‘technical cycles’ (where the ‘Hierarchy of Waste’ – i.e. prevent-reduce-reuse-recycle-recover-dispose – is key to circularity) and ‘biological cycles’ in society, and the key roles of EfW in both energy recovery from these two cycles (to feed-back renewable energy – power and heat – into both cycles) and, via biological treatment processes such as anaerobic digestion (AD), to produce biogas and even biomethane.

All of these integrated notions have been pulled together recently in an excellent report on ‘Energy from Waste and the Circular Economy’ published in the UK by the Energy Research Accelerator (ERA) together with the Birmingham Energy Institute at the University of Birmingham. In 2019, these organisations jointly established the Energy from Waste and the Circular Economy Policy Commission to examine the state of play, barriers, challenges, and opportunities for EfW in the UK, and how the Midlands region, in particular, can take advantage of its industry, facilities and expertise in energy to become a global leader in this area. Chaired by Lord Teverson, the Commission consists of leaders from industry, academia and the public sector, who, over a period of several months discussed the issues and challenges, explored the potential technological solutions and took evidence from a range of experts.

The UK, like many other countries, lacks the capacity to deal with all the waste it produces and exports millions of tonnes overseas. But now countries in the Far East are banning unwanted shipments from developed countries and tariffs are being introduced in European countries such as the Netherlands. For some, the answer is clear: we need a ‘circular economy’ with much higher levels of recycling, which both conserves resources and cuts CO2 emissions. If we achieve that, they argue, we won’t need EfW plants, which are mostly incinerators that generate only electricity, because we won’t have any rubbish left to burn. Worse, they claim, the very existence of incinerators discourages recycling, so we must get rid of them.

I don’t think any of us would argue with the pressing need to raise recycling rates… but the choice is not a binary one.

Changing large infrastructure systems takes time. There is already a steady move towards thermal treatment processes for wastes (i.e. incineration) that operate in a combined heat and power mode – not just a power mode. Also, advanced thermal processes (based on pyrolysis and gasification technologies) are beginning to be built – particularly as a solution for difficult wastes such as plastics. Also, biological treatment processes (particularly AD units producing biogas or coupled with upgrading technology to produce biomethane) are on the increase. All of these options could play an integral part in the circular economy.

Furthermore, however high we manage to raise recycling rates – currently stuck at about 45% in the UK – there will always be some residual waste. In some ways, this may not be a problem but an opportunity. EfW will always be necessary but must be made more ‘circular’ and lower emitting.

The EfW Policy Commission are convinced that with the right changes in policy the industry can plot a path to become zero-emission and resource-efficient by 2050. With far higher recycling rates, it will be a smaller industry than today but potentially more valuable. It will certainly be more integrated with recycling systems and local economies. National policy reforms must include a more Scandinavian approach to capturing heat, major public investment in infrastructure and strengthened support for R&D and venture capital stage technologies. Together this would greatly improve resource efficiency; start to decarbonise heat, one of our toughest challenges; and set EfW on course to reach net-zero by 2050.

The Policy Commission have proposed three major areas where it believes that government investment would be highly beneficial:

- Building a network of local and regional ‘Resource Recovery Clusters’ (RRCs)

- Creating a ‘National Centre for the Circular Economy’

- Launching an R&D ‘Grand Challenge’ to develop small-scale circular carbon capture technologies.

The RRCs would combine a spread of EfW and recycling technologies with businesses that can consume their cheap electricity, heat, fuels, CO2 and material outputs. They could be developed on post-industrial sites, offering significant environmental, economic and regeneration benefits.

![]()

The proposed National Centre for the Circular Economy would analyse material flows throughout the economy down to regional and local levels, and develop deep expertise in recycling and EfW technologies.

The R&D Grand Challenge concept would aim to make big advances in small-scale carbon capture technologies in order to turn 100% of CO2 produced through the process of converting waste to energy into useful products. This is very important for areas such as the Midlands which are remote from depleted oil and gas reservoirs.

Speaking about the ‘Energy from Waste and the Circular Economy’ report, Lord Robin Teverson, Chair of the EFW Policy Commission, said: “The management of waste is a huge issue not just in the UK, but globally. With the academic and industrial expertise that we have in energy and waste processing in this country, we believe that with carefully targeted investment into the three areas we have identified, the UK would be perfectly positioned to be a global leader in this field, both industrially and academically. This will help to create many new businesses and jobs at old industrial sites both in the Midlands and across the country.”

Professor Martin Freer, Director of both ERA and the Birmingham Energy Institute, added: “We need to start thinking of the management of waste not as a huge problem but as a huge opportunity. There are already great examples of where this is happening, such as the Tyseley Energy Park in Birmingham, where a relatively small investment from government via ERA, and also the University of Birmingham, has provided the catalyst for a major energy from waste innovation zone to be created. In the East Midlands, we believe that the redevelopment of the Ratcliffe on Soar power station provides a fantastic opportunity for a large Resource Recovery Cluster to be created. Through ERA we have a partnership of over 1000 energy researchers and academics, and a network of industrial partners. We are ready and able to support the government in ensuring that the UK leads the world in energy from waste and circular economy.”

If this topic interests you, why not join in a free online event about this report on Wednesday 29th July? To register for this webinar, see here