-

What are the cement manufacturing processes?

Date posted:

-

-

Post Author

dev@edge.studio

1. Introduction

The complete range of processes undertaken in the minerals processing industry was outlined in CF 255. This combustion file gives more specific detail of the processes in use for the manufacture of cement.

2. Cement

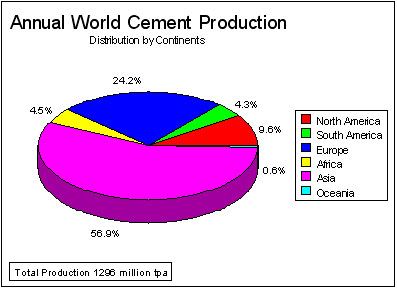

The manufacture of [GLOSS]cement[/GLOSS] consumes the major proportion of the world’s processed limestone, and is almost exclusively made in rotary kilns, with the exception of some shaft kilns in China and eastern Russia. Figure 1 shows the market breakdown by continents in 1993.

The manufacture of cement involves the same initial reactions as those of lime production, but this is followed by a series of complex, higher temperature, exothermic reactions in which alumina, silica and iron are [GLOSS]flux[/GLOSS]ed into [GLOSS]cement clinker[/GLOSS]. These fluxing reactions do not occur until the calcined material reaches ~1350oC, and because they require a semi-molten state with a carefully controlled time/temperature profile, these reactions are ideally achieved in a rotary kiln. The fluxed state of the material in the burning zone of the kiln results in the build up of a coating on the inside refractory. This is beneficial for refractory life if it is controlled, but excessive fluxing, or local ash, [GLOSS]alkali metals[/GLOSS], sulphur or chlorine deposition results in restrictive [GLOSS]rings[/GLOSS] being formed. Rapid cooling of the clinker is required to produce the best quality cement. The significant advantages of high production capacity was the primary driver for the development of the rotary kiln in the cement industry, and current modern plant are built to produce up to 10,000 tpd using [GLOSS]precalciner[/GLOSS] systems in which 40-50% of the fuel is burnt in the kiln, and the balance in the precalciner.

The original rotary cement kiln technology used a short dry kiln, but this was rapidly superseded by long wet kilns using a wet [GLOSS]slurry[/GLOSS] feed of 35-40% moisture. This process has a specific fuel consumption of 6.5 – 8.5 MJ/kg due to the thermal drying penalty in the [GLOSS]chain drying[/GLOSS] section at the ‘back end’ of the kiln. The long dry kiln, in which powdered ‘[GLOSS]raw meal[/GLOSS]’ is fed to the kiln, was prevalent in North America until the latter part of the 20th century, with a specific fuel consumption of 5.0 – 6.5 MJ/kg. The introduction of the [GLOSS]grate preheater[/GLOSS] (Lepol) kiln in the 1930’s, which is fed with [GLOSS]nodulized[/GLOSS] ([GLOSS]semi dry[/GLOSS]) or extruded ([GLOSS]semi wet[/GLOSS]) material reduces the specific fuel consumption to 4.0 – 4.5 MJ/kg. Further improvements in fuel usage (3.5 – 4.0 MJ/kg) were achieved in the 1950’s with the introduction of the [GLOSS]suspension preheater[/GLOSS]; a series of counter-flow cyclone heat exchangers fed with a dry powdered meal, at the back of a short rotary kiln; and the introduction of a precacining chamber between the preheater and kiln results in current specific fuel consumptions of 3.1 – 3.4 MJ/kg. All of these kiln technologies are still in use today.

Figure 1 World Cement Production for 1993 (Cembureau)

Like lime, finished cement is rarely transported very far from its point of manufacture to its customers, although cement clinker is shipped around the world on a reasonable scale, both between plants and to dedicated grinding plants in strategic locations, to provide finished cement where raw materials or the market size do not justify a complete operation. The selling price of bulk cement is similar to that of bulk lime.

Sources

[1] World Cement Directory 1993, Cembureau