-

What is petroleum?

Date posted:

-

-

Post Author

dev@edge.studio

1. Introduction

The word petroleum literally means ‘rock oil’, as it is normally found underground in porous rocks, usually accompanied by gas. It is often used synonymously for ‘[GLOSS]Crude Oil[/GLOSS]’, ‘[GLOSS]Crude Petroleum[/GLOSS]‘, or simply ‘Oil’.

Petroleum is a dark coloured liquid with the potential to release energy to generate heat through [GLOSS]combustion[/GLOSS], and is the source of a wide range of industrial liquid fuels for process heating and power generation – see CF62 for an introduction to petroleum as an industrial fuel.

Though its composition varies with geological location, a general indication of the chemical composition (by weight) of petroleum would be: C(84%); H(14%); S(1-3%); N(<1%); O(<1%); metals and salts (<1%).

The value of petroleum is due to its ease of storage, transportation, utilisation, high stored-energy density and relative ease of conversion to thermal energy. The primary use of petroleum fuel is for transportation, with industrial process heating and power applications also accounting for significant consumption.

2. Formation of Petroleum

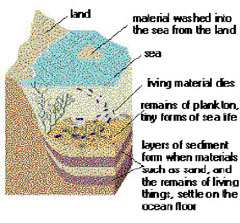

The vast majority of our energy sources – including petroleum – are derived from the Sun. Petroleum is the remains of earlier vegetation and animal life, deposited as time-stored [GLOSS]Fossil Fuel[/GLOSS]s.

The age of the Earth is believed to be over 2000 million years, with the accumulation of energy via the deposition of eventual fossil fuels believed to have commenced some 500 million years ago, during the last quarter of Earth’s lifetime.

The parent materials of petroleum are considered to be marine in origin, and the transformation from marine deposits to liquid fuel are assumed to be partly chemical in nature, and partly due to anaerobic bacteria.

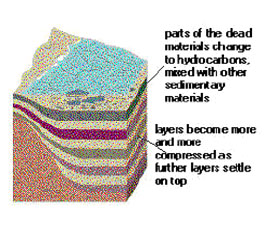

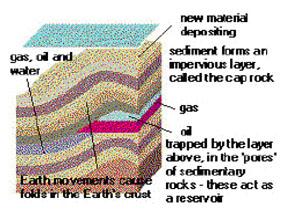

Once formed, petroleum migrates through porous strata under the action of its own surface-tension forces and gas pressures, until it is either lost to the atmosphere or held by an impervious ‘cap rock’ layer acting as a seal (See Figure 1). Due to the migration from source rock to reservoir rock, the geological history of a petroleum deposit is often difficult to trace.

(a) (b)

(c)

Figure 1: Formation of Petroleum

3. Man’s Utilisation of Petroleum

Man’s utilisation of petroleum fuel has been intermittent over the last 5000 years. What could be called the first oil era, between 2500-1000 BC, took place during the Babylonian Era, when use was made of oil seepages, or shallow deposits, as a fuel to fire high temperature processes such as the manufacture of terra-cotta.

Subsequent generations established small industries for distillation of oil from shale, tar-sand and coal, driven primarily by the need to find superior fuels to [GLOSS]bio-oils[/GLOSS] and the dissatisfaction with artificial illumination. However, it wasn’t until Edwin Drake of Titusville (Pennsylvania) drilled a well specifically to locate oil in 1859, that the second – current – oil era commenced in earnest. Drake discovered petroleum at 69 feet and produced at the rate of 800 gallons per day.

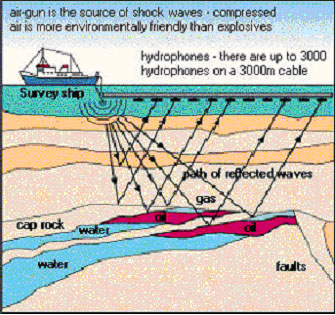

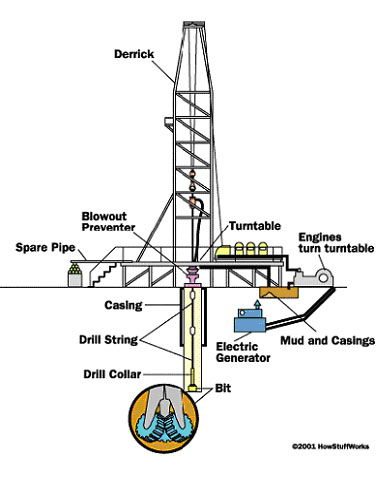

Increased supply of oil through advanced exploration (See Figure 2) and production techniques (See Figure 3), coupled with a concurrent increase in demand due to technological advances such as automotive transport, flight and electrical power, provided fertile economic conditions for the second oil boom. This led to annual world consumption of billions of tons of petroleum within 100 years of Drake’s first well.

Figure 2: Advances in Oil Exploration

Concern over the finite lifetime of fossil fuel reserves (estimated at 30 years in 1975), together with the increasing rate of consumption, and the disproportionate distribution of known world reserves, contributed to the so-called ‘Energy Crisis’ in the early 1970s.

However, exploration and production improvements led to significant oil finds in various other geographical locations in the last quarter of the 20th century, with very significant finds in the North Sea, Africa, the Far East, South America and Alaska.

Figure 3: Advances in Oil Production Technology

Environmental concerns have provided more recent challenges to petroleum utilisation, with significant international pressure to move away from reliance on fossil reserves such as petroleum products to more sustainable energy options.

International summits during the 1990s (the ‘Rio’ and ‘Kyoto’ summits) have attempted international co-ordination of policy. However, whilst the move towards use of sustainable energy forms is inevitable, liquid fuels are still likely to play a dominant role in the first half of the 21st Century.

4. Petroleum as a source of industrial fuels

In CF62, petroleum derived industrial fuels are broadly categorised as [GLOSS]Petroleum Distillate Fuels[/GLOSS], essentially “light” fuels, and a range of [GLOSS]Petroleum Residual Fuels[/GLOSS] broadly described as light, medium and heavy oils. These two categories comprise a very wide range of fuels, which are detailed in CF233, along with information on the derivation of these fuels from crude petroleum.

Sources

[1] Goodger E.M. ‘Hydrocarbon Fuels’, 1975

[2] Lefebvre A.H. ‘Atomisation and Sprays’, 1989

[3] Goodger E.M. Journal of Institute of Energy, 1997

[4] Kempe’s Engineers Year-Book, Ed. J Hall Stephens (2002)

[5] Combustion of Sprays of Liquid Fuels, Alan Williams (1976)

[6] Robert H. Perry-Don W.G, Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, 1976

[7] Elsevier science publishing, Shell International Petroleum Company, The Petroleum Handbook, 1983.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Peter Kay (Ricardo-Sponsored PhD Student) and Anthony Giles (EU/EPSRC sponsored PhD student) for their assistance.