-

COP26 – How much of what needed to happen transpired?

Date posted:

-

-

-

Post Author

Patrick LaveryCombustion Industry News Editor

-

-

![]()

In September, IFRF published an analysis of the current state of play in regards to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and international agreements to reduce them. Before COP26, a number of countries/trading blocs had already announced ambitious GHG reduction goals for 2050 and intermediate ones for 2030, including the EU and USA, Japan and South Korea. China had announced a 2060 goal for ‘carbon neutrality’ which was much welcomed and highly important, albeit not 2050. Despite this, if all major emitters met their then 2030 targets, the world would still have seen a net increase in GHG emissions, and this would probably have meant that the generally accepted 1.5°C target for a maximum in global average surface temperature rise would be exceeded during the 2030s.

As a recap, what was concluded was that:

- Target-setting leads to reductions and technological development. Though there are exceptions, governments tend to try to honour their commitments, and in doing so they spur technological change by setting conducive policy environments.

- In the past, some countries had made commitments to reduce GHG emissions in relative terms, for example by a percentage less than ‘business as usual’. These were essentially junk pledges, as ‘business as usual’ was typically defined as an implausibly high-growth scenario. Because there is, in effect, a budget for the amount of additional GHGs that can enter the atmosphere before the 1.5°C target is exceeded, absolute targets needed to be set.

- There could be more leeway for developing countries for intermediate (2030/2035) targets than for developed countries. This would mean that technologies across all sectors would be brought to maturity by developed (and middle-income) countries over the next 10-15 years and then deployed in developing countries to help speed-up emissions reductions. This would go some way to meet the need for fairness across countries.

Arising from these conclusions, the IFRF thought-piece went on to identify six outcomes that were considered as necessary to be achieved if COP26 was to be considered a success. These necessary outcomes are listed in the table below (italics), along with summary information on what was announced.

1 The most important single new target at Glasgow would be for China to peak its emissions in the middle of this decade, but India’s announcement of the same would be second. 2030 announcements postponed to November 2022. 2 Developed nations should pledge only to reduce (from 2019 levels) from this year onwards if they are not already reducing emissions. No firm announcement on this. 3 All countries should set a net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 target. If not all countries quite meet this, it would still give the world a chance of meeting the 1.5°C target. India set a net-zero by 2070 target; Russia and Saudi Arabia set net-zero by 2060 targets;

Australia, Vietnam and Brazil set net-zero by 2050 targets;

Turkey set a net-zero by 2053 target;

China and the USA agreed to cooperate on climate mitigation measures, including methane emissions, the transition to clean energy and de-carbonisation, and to do so this decade;

Iran and Mexico did not set a target.

4 Developed and middle-income nations without ambitious 2030 goals would have to set them. This was particularly true of Australia and Saudi Arabia as developed countries, and Russia, Mexico, Brazil, Iran and Turkey as middle-income countries. All bar Iran are members of the G20 and had already pledged to announce new targets in the run-up to Glasgow. The question was if they were ambitious enough. 2030 announcements postponed to November 2022. 5 Of the richer nations with established 2050 net-zero targets, there was a need to increase support to developing nations to fund GHG emissions reduction projects. Richer nations are to “at least double” their financing of climate mitigation measures in developing countries, with the prospect of a trillion dollar per year fund from 2025. The latter prospect would generally be considered something like sufficient funding. 6 All countries needed to agree to a target to bring aviation and shipping emissions to zero by 2050 or 2060. Only partially addressed – detail below. So, against these objectives, how did COP26 do?

Intermediate term (2030-35)

The intermediate term was the most vital area for announcements at COP26.

The decision to postpone 2030 goal-setting until COP27 in Egypt, which is to take place in November 2022, means that some of the most important national objectives have not been met, although there is still a chance they may be in the relatively near term. (Brazil did set a goal of reducing its GHG emissions by 50% this decade.) COP26 must be seen as a disappointment in this regard, however, even if such ‘can-kicking’ could have been expected.

However, initiatives at the sector level, as opposed to the holistic level, were more encouraging.

- More than 100 world leaders agreed to end and reverse deforestation by 2030, a highly significant achievement given the large role land-use change plays in GHG emissions. Russia and Brazil were amongst the signatories, as were Canada, China, Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Ivory Coast, the USA and Australia.

- A separate grouping of 105 countries pledged to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2031, but this did not include China, India, Russia, Iran and Australia.

- More than 40 countries made a commitment to “cease issuance of new permits for new unabated coal-fired power generation projects, cease new construction of unabated coal-fired power generation projects and to end new direct government support for unabated international coal-fired power generation”. Of those 40 countries, 23 had previously not made such a commitment, including Poland, Vietnam, Chile, Morocco, South Korea and Ukraine.

- A framework was agreed, after six years of development, for the global trading of carbon-equivalent credits.

- Commitments from China, Korea, Japan, the USA and 16 other countries to end financing for foreign coal projects were reiterated.

Long term (2050-70)

Much of the world now has a net-zero target, although there are notable exceptions, and for some countries the targets lack detail and/or still need to be legally adopted. In addition, some countries without targets and with relatively small GHG outputs at present may increase them fairly rapidly with economic growth, and those countries will come under pressure to set targets.

Aviation and shipping

A coalition of ‘original equipment manufacturers’ in the aviation industry made a net-zero by 2050 commitment. Separately, the International Aviation Climate Ambition Coalition of 23 nations that together produce 40% of emissions pledged to take action consistent with the 1.5°C target. However, China, Germany, India, the United Arab Emirates and Australia were not part of this scheme.

Fourteen countries signed a declaration calling on the International Maritime Organization to align its 2050 target (which is currently a 50% reduction) with the 1.5°C target. More significantly, 19 countries joined the Clydebank Declaration to create zero-emission ocean shipping corridors, including the USA, Japan, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, the UK and Australia. In the words of Splash247, the “corridors approach enables governments to first incentivise and, eventually, require that only zero-emission ships can travel from, say, Shanghai to Los Angeles or Rotterdam to New York.”

Thus the commitments in regards to aviation and shipping can only be considered partially sufficient. An optimistic appraisal is that technological development will be spurred by policies that will come out of the commitments, and that such technology will be able to be applied more broadly in the future. Such a picture would keep 2050 or 2060 next-zero a possibility for shipping and aviation.

Overall

COP26 can be seen as partially successful. The most worrying sign for the global climate is probably that intermediate GHG reductions targets have not been improved in the countries that really needed to improve them, and so much now rides on COP27 in November 2022. Right now, it appears that emissions are set to rise throughout the 2020s. The most promising signs are that most countries now have long-term net-zero targets, that a framework for global carbon trading is in place, that financing to developing nations is to increase significantly and possibly even to levels ‘in the right ball park’, and that there are intermediate initiatives to reduce methane emissions and reverse deforestation. In addition, there appears to be commitments in place for most sectors, including aviation and shipping, to develop the technologies that will make net-zero by mid-century a possibility.

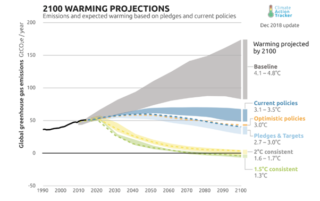

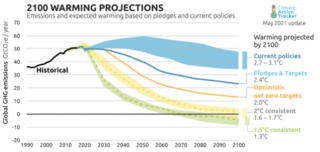

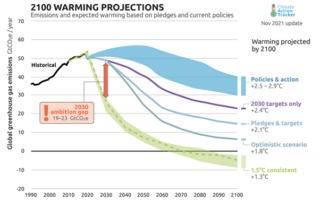

A different measure to assess overall progress is to look at how Climate Action Tracker’s warming projection charts have changed over time. COP26 moved the ‘optimistic scenario’ projection from 2.0°C to 1.8°C. The gap to 1.5°C has narrowed, and from the perspective of 2015, this would be considered an unqualified success, given that 2.0°C was the headline target in Paris, when the world looked on course for 2.7°C at best. However, it is now 2021, climate change has become an even greater priority for many across the world, and there is greater understanding of the difference between 1.5°C and 2.0°C. COP27 will see if the ‘2030 gap’ identified by Climate Action Tracker will narrow further. My suspicion is that COP27, too, will be only partially successful, but there is substantial room for countries such as China, India and Australia to considerably improve their intermediate targets.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figures: 2100 warming projections – from December 2018, May 2021 and November 2021 (ClimateActionTracker.org)