-

IPCC releases Physical Science Basis component of Assessment Report 6

Date posted:

-

-

-

Post Author

Patrick LaveryCombustion Industry News Editor

-

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has released the first part of its Sixth Assessment Report (which is due to be published in full in 2022), this part being ‘The Physical Science Basis’. Amongst the findings are that:

- Carbon dioxide levels in 2019 were higher than at any point in at least 2 million years.

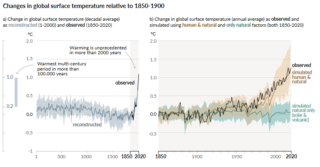

- Global average surface temperatures have been 1.09°C higher [the confidence range being 0.99-1.20°C] between 2011-2020 than between 1850-1900. Land surface temperatures have been on average 1.59°C higher, and ocean surface temperatures 0.88°C higher.

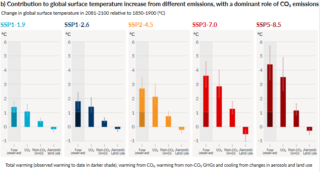

- The best estimate is that of the 1.09°C rise, 1.07°C was caused by human activity. This is a net effect of greenhouse gases causing heating and aerosols causing cooling (mostly through depletion of stratospheric ozone).

- Between 2006 and 2018, sea levels have risen an average of 3.2-4.2mm/yr, an accelerated rate compared to 1971-2006, which itself was higher than the period 1901-1971.

- Annual average Arctic sea ice coverage was lowest between 2011-2020 than at least since 1850. Antarctic sea ice coverage, however, has exhibited no trend between 1979 and 2020 due to “regionally opposing trends and large internal variability”.

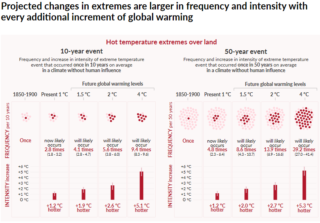

- “Climate change is already affecting every inhabited region across the globe, with human influence contributing to many observed changes in weather and climate extremes”. Heatwaves, extreme precipitation, cyclones and droughts have all become more extreme/frequent in recent decades (to varying levels of confidence).

- “The observed average rate of heating of the climate system increased from 0.50Wm–2[0.32 to 0.69] for the period 1971-2006, to 0.79Wm–2[0.52 to 1.06] for the period 2006-2018 (high confidence). Ocean warming accounted for 91% of the heating in the climate system, with land warming, ice loss and atmospheric warming accounting for about 5%, 3% and 1%, respectively (high confidence).”

- Climate sensitivity – the amount of global surface warming that will occur in response to a doubling of atmospheric CO2 concentrations compared to pre-industrial levels – is estimated at 3°C, with a range of 2.5°C to 4°C at high confidence.

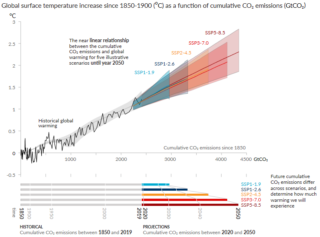

- “Each 1000GtCO2 of cumulative CO2 emissions is assessed to likely cause a 0.27°C to 0.63°C increase in global surface temperature with a best estimate of 0.45°C.” This is close to being a linear relationship, rather than an exponential one, fortunately.

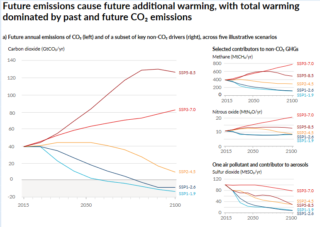

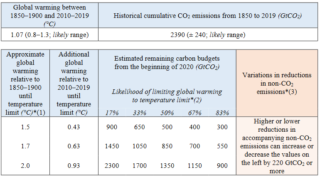

A number of scenarios are presented to predict temperature rises to the 2081-2100 period based on GHG and aerosol emissions up until that time. In the most optimistic scenario of almost achieving net-zero CO2 emissions globally by 2050 (and significantly lower other GHGs), and then ‘negative emissions’ from about 2055 onwards, average surface temperature rises would be confined to 1.4°C at the best estimate (very likely between 1.0 and 1.8°C). The second most optimistic scenario has about a halving of GHG emissions by 2050, reaching net-zero by 2075, and negative emissions after that, which it is estimated would result in 1.8°C at the best estimate (very likely between 1.3 and 2.4°C) by 2100. In the worst of the five cases, GHG emissions balloon to triple current levels by late in the century, resulting in average surface temperature rises of 4.4°C at the best estimate (very likely between 3.3 and 5.7°C).

While the differences between 1.4°C and 1.8°C may seem small, the IPCC published an entire report on the difference in impacts between 1.5°C and 2.0°C in 2018, and they are substantial. All scenarios, however, carry impacts, illustrated by the fact that it is expected that regardless of which scenario the future most closely matches to, it is likely that there will be no Arctic sea ice in September at least once before 2050. Impacts are already occurring, of course, as the terrible fires in the Eastern Mediterranean and California in recent weeks have shown.

The new report is stark, a “code red” on the state of the climate. However, the modelling does offer the hope that achieving net-zero, or something close to it by 2050, with negative emissions thereafter will allow the world to meet the more ambitious target of the Paris Agreement of limiting temperature rises to 1.5°C. The remaining carbon budget to do so is very narrow, however. At 2019 rates (of around 40Gt/yr of CO2 equivalent), this could mean 1.5°C is reached as soon as 2029 – only 7.5 years away, although more likely is 2034 (a 50% chance), and there is a 33% chance it could stretch to 2037. The upshot is that emissions must decline within a few years if they have not already peaked, and fall sharply thereafter. If falling linearly (the most optimistic IPCC scenario is roughly so), this would be an emissions reduction of around 1.6Gt per year. If one was to assume coal-fired power generation produces 0.9kg of CO2 per kWh, and assuming a capacity factor 0.6, this would mean the closure of 451 coal-fired power plants of a 750MW rating (338GW of total capacity), year-on-year.

In the words of Dr Friederike Otto of the University of Oxford, a contributor to the report, “We are not doomed.” But scientists, engineers, technicians, administrators, politicians, economists, entrepreneurs and a wide variety of others will therefore have to work very hard on meeting reduction targets over the coming decades.

As the report makes clear, action must begin now, and many hopes will be riding on the COP26 climate conference in November to feature ambitious new announcements that will be backed by policy.